Diego Rivera (December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was more than an artist, he was a force of nature. A master-inventor of a visual language created specifically to articulate the diverse heritage of Mexican people, he crafted images of Mexico’s historical development and cultural ethos that defined its identity for its citizens and for the larger world.

Diego Rivera (December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was more than an artist, he was a force of nature. A master-inventor of a visual language created specifically to articulate the diverse heritage of Mexican people, he crafted images of Mexico’s historical development and cultural ethos that defined its identity for its citizens and for the larger world.

Rivera is now the subject of a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art” reunites five murals he was commissioned to paint by MoMA in 1931. It opens Sunday, November 12 and runs through May 14, 2012. The installation marks the first time in 80 years the murals have been brought together.

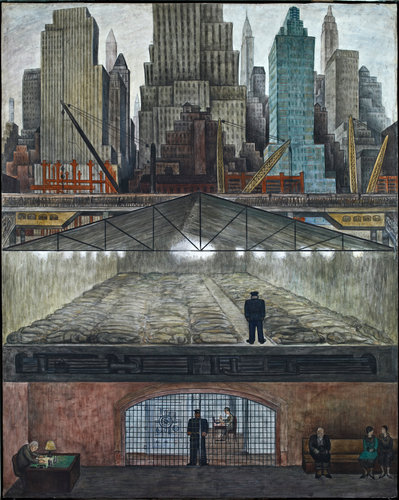

Below is “Frozen Assets,” one of the five murals that will be on display. The upper section depicts skyscrapers and construction cranes rising above Manhattan Island in the midst of the Great Depression. In stark contrast, a homeless shelter occupies the center of the space. The rows of sleeping men resemble corpses buried beneath the marvels of modern technology. Their massed bodies suggest they are victims of progress or perhaps the human sacrifices that made it possible. In the foreground, a lone police office stands sentry as if to prevent their resurrection. The bottom section provides yet another clever juxtaposition of thematic material. It depicts the leading American tycoon of the era, John D. Rockefeller Jr., ensconced bunker-like in a bank vault. Sitting hunched over at his desk, Rockefeller works within a few steps of the immense wealth that is the source of his power and prestige.

On the skyline above, in the shelter below, and in the bank vault beneath it all, the material, human, and capital “assets” of America are captured and portrayed by Rivera in an austere moment “frozen” in time.

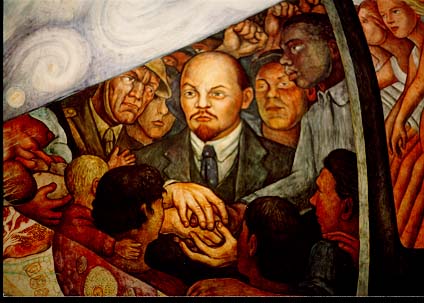

Rivera’s artistic vision for his massive mural projects lacked the inhibitions to which many artists would have surrendered in designing and composing works commissioned by the wealthy elite who were the principle patrons of the arts. He was a communist. His brushstrokes spoke truth to power, as was the case when he included the figure of Vladamir Lenin in the mural he designed for the lobby of Rockefeller Center. The project—which commenced a few years after the MoMA commission—halted abruptly after he refused to substitute another face for Lenin’s. Rivera was paid his fee in full and the building management, which abhorred Rivera’s “agit-prop” artistic style, ordered drapes hung over the unfinished work. Negotiations took place to transfer the mural to the MoMA. But on February 10, 1934, building mangers dispatched a team of workmen at midnight with orders to dismantle it. They smashed the work to pieces with axes and stuffed the remnants into oil drums. Rivera’s career as an international muralist nearly ended at that moment. Not a man to allow others to have the last word, however, especially those who he accused of “cultural vandalism,” Rivera painted a replica of the mural at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City into which he also slyly inserted an image of John D. Rockefeller drinking a martini while the masses toiled away.

During his time in New York—which coincided with the literary and artistic era known as the Harlem Renaissance—Rivera visited Harlem, frequented the Savoy Ballroom, and met numerous black artists and intellectuals. Among them he associated with a young artist named Charles Alston (1907–77). Alston, a frequent visitor to Rockefeller Center to view the mural’s progress, also supported and joined the demonstrations protesting the project’s termination. Rivera became an important influence in Alston’s work, which took on a greater significance in 1936, when he was chosen to direct a mural project under the auspices of the Federal Art Project. The Harlem Hospital Center WPA Murals were the first major U.S. government commissions awarded to African American artists, and Alston was the first African American project supervisor of the Federal Art Project. Alston, who also was an illustrator and cartoonist, later became the first African American to teach at MoMA.

During his time in New York—which coincided with the literary and artistic era known as the Harlem Renaissance—Rivera visited Harlem, frequented the Savoy Ballroom, and met numerous black artists and intellectuals. Among them he associated with a young artist named Charles Alston (1907–77). Alston, a frequent visitor to Rockefeller Center to view the mural’s progress, also supported and joined the demonstrations protesting the project’s termination. Rivera became an important influence in Alston’s work, which took on a greater significance in 1936, when he was chosen to direct a mural project under the auspices of the Federal Art Project. The Harlem Hospital Center WPA Murals were the first major U.S. government commissions awarded to African American artists, and Alston was the first African American project supervisor of the Federal Art Project. Alston, who also was an illustrator and cartoonist, later became the first African American to teach at MoMA.

The mural section depicted below by Charles Alston is titled: Magic in Medicine. It juxtaposes images of traditional West African medical practices with modern medical practices depicted in its opposite in the series titled Modern Medicine. The focal point of the scene is the representation of a Fang sculpture rising above dancing, drumming, and healing rituals taking place below.

In 1939 Rivera hired African American Artist Thelma Johnson Streat to work with him on his Pan American Unity Murals in San Francisco. Streat, also a force a nature, was a dancer, folklorist, textile designer, and visual artist who worked in oil, watercolor, charcoal, and mixed media. She often portrayed notable figures from the African Diaspora in her compositions, and once received threats from the Klu Klux Klan for her painting “Death of a Negro Sailor” for its depiction of a black sailor sacrificing his life in the war abroad to protect a country that refused to recognize his rights at home.

In 1939 Rivera hired African American Artist Thelma Johnson Streat to work with him on his Pan American Unity Murals in San Francisco. Streat, also a force a nature, was a dancer, folklorist, textile designer, and visual artist who worked in oil, watercolor, charcoal, and mixed media. She often portrayed notable figures from the African Diaspora in her compositions, and once received threats from the Klu Klux Klan for her painting “Death of a Negro Sailor” for its depiction of a black sailor sacrificing his life in the war abroad to protect a country that refused to recognize his rights at home.

Rivera, who included figures representing the African presence in Mexico’s history in his paintings, also had an African presence in his family tree. And his depictions of Mexican people, in general, were painted in rich brown tones in recognition of their mixed Native American, African, and European heritage. Rivera’s vision of Mexico’s past, which remains fundamental to its cultural identity, nevertheless, has been obscured and even hidden in a modern Mexico that prefers to see its image in the bleached blonde blanquitas that dominate the nation’s popular television shows and advertising. However, unlike the remnants of the monumental architecture of Tenochtitlan Mexico (the capital of the Aztec Empire), which long since have disappeared beneath modern Mexico City, Rivera’s paintings remain as a constant reminder of a past that is still present in the faces of Mexico’s people.

November 24 marks the 54th anniversary of Rivera’s death. But his legacy as an artist and force of nature lives on.

I do not think that the capacity for artistic expression has anything to do with race or heredity. Opportunity, merely. In this civilization we are more crowded, more hurried, and we are made to do from childhood many things we do not want to do, so that what is creative is killed, at least it is forcibly turned into other channels than the artistic because of the pressure against true artistic expression. So people of this civilization express their emotions in other ways than in art, and it is a very poor place for the artist to function. In the South or far North where there is not always the system saying do this, do that, there it is easy for them to make art because they do not know that they are artists and that art is something apart from life, and that to make it one must be either a genius or crazy. They make it because they love the animals, they hunt them for food, they kill them, their emotions are bound up in the animals –and so they put this emotion into these little carvings. They have not had their emotions squeezed out of them and so they can function as artists.

Source: Dorothy Puccinelli’s interview with Diego Rivera, San Francisco 1940)

Fabulous e hoa – this art is amazing, and I had never heard of Diego Riviera before. I could gaze at these paintings for hours. Makes me wish I’d studied art history. So much to know, so little time/space/energy. Thanks for bringing a slice of it here so I can view it admiringly from afar!

You should also check out the work of his wife Frida Kahlo. She was a truly inspired artist: http://www.fridakahlofans.com/

Oops forgot, your post reminds me of one of my favourite James Baldwin quotes: Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, make freedom real.

Love the Baldwin quote!

Wow…his work is amazing! In my quest to learn more about my Mexicam history, I plan on catching the train over to NYC with my children to see this exhibit. Thanks for sharing this info.

I’m thinking about going to NYC to catch the exhibit in the early spring.